Knowledge to policy (K2P) is a popular term to describe the way research and other types of knowledge inform policy-making. K2P processes and systems aim to support decision-makers to create good policies that make a difference to people’s lives.

The K2P sector includes knowledge producers (such as policy research institutes or think tanks), organisations that use knowledge (such as government ministries and line agencies), and those working in the space between (such as advocacy groups or policy analysts).

Recently, I’ve heard more and more people in the sector talking about the need for a ‘K2P framework’.

While it’s tempting to look for an all-encompassing framework, this is an elusive search. Even if we do find or develop one, it would be so complex and unwieldy that it would surely be unusable.

Instead, we need to develop ‘sub-K2P frameworks’, which will help us to break down the complexities and organise our ideas and planning.

A recent workshop with over 100 participants from across Indonesia’s K2P sector (including researchers, civil servants, advocates, and development practitioners) highlights this point.

The workshop divided into five working groups: 1 – frontline service delivery 2 – village law and service delivery 3 – bureaucratic reforms 4 – research financing 5 – K2P processes and systems.

I joined group five, with approximately 25 other interested people. We developed a list of K2P activities. The list included things like political economy analysis, big data, knowledge repositories, strategic communications and writing skills.

The group decided that strategic communications should be top of the priority list.

While I agree that strategic communications is important, I questioned our seemingly arbitrary placing of it at the top of the list. Does creating such a hierarchy suggests that communications can be seen in isolation from other policy influence activities?

I presented to the group a simple framework shown to me by former ODI director Simon Maxwell. During a meeting, Simon drew four axes to describe four competency areas required by a policy research organisation such as ODI:

Organisations wanting to inform and influence policy and public debate need to:

- know how to do good research;

- know how to present and package their research findings for different audiences;

- know how policy-making systems work and be willing to engage with it; and

- be involved in networks that can help to join forces and channel policy advice and evidence.

This simple framework shows that, while strategic communication is important, it can’t be seen in isolation. It’s part of a process that involves good context analysis, stakeholder analysis, planning and networking.

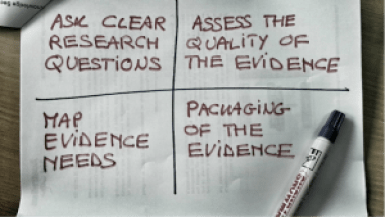

But this is only part of K2P processes. What about policy makers – what would a similar competency framework look like for them? Perhaps something like this:

Mid-level civil servants would need to know:

- how to ask ‘good’ research questions that meet their evidence needs;

- how to assess the quality of the evidence they receive;

- be clear about the format evidence should be presented to them in; and

- how to map the evidence the institution already has versus the evidence it requires.

These are just two examples of practical ‘sub-K2P-frameworks’. There are many other tools and frameworks out there and more are needed to continue our efforts to navigate problems and solutions. The RAPID Outcome Mapping Approach (ROMA) to policy engagement, Ingie Hovland’s M&E framework for policy research influence, or Harry Jones’s Knowledge Politics and Power framework, help to bring existing tools together.

And so, while it is tempting to search for an all-encompassing K2P framework, or some other infallible solution, K2P is a complex, messy business that requires adaptation and multiple solutions. As Tim Harford writes ‘success starts with failure’. K2P sub-frameworks are the starting point, to help us organise and plan. By breaking it down, we can unfold the complexities and produce maps of variations, learning and adapting as we go.

Social Media